THE ZELNIK COLLECTION

OF KHMER TEXTILES

AND WEAVING IMPLEMENTS

by Gillian Green

This essay introduces textiles and weaving implements in the Zelnik collection. Publishing such a large collection of items affords a rare and invaluable resource as the more information and images in the public domain, the more deeply can this important and often overlooked aspect of Khmer culture and history be explored and researched.

Though there are no existing examples of ancient textiles, the Khmer textile tradition can be traced back many centuries, by examining the dress sculpted on the celebrated sculptures of the Angkorian period – 7th to late 14th century. During this time it is most likely that the majority of textiles depicted as hipwrappers were not only sourced in India but also that their styles were adapted from the Indian tradition. The fabric used was probably cotton, indicated by comparison of patterns with those of contemporaneous Indian cotton textiles. Chinese silk was, however, also known to have reached the Khmer court in the latter part of this period but pattern analysis suggests those were only used as items of interior décor or for personal accessories.

Though the Khmer kingdom was geographically distant from the Indian subcontinent, contact was not as remote as it may seem. Indian merchants had plied maritime trade routes from at least the early first millennium, navigating the Indian Ocean coastline to the Malay Peninsula. Their textiles were among the high value commodities that found their way to Southeast Asian courts. These were traded for highly desired forest products. By the nineteenth century, however, textiles themselves, made in Cambodia, begin to appear in collections affording researchers at least a start point.

The most distinctive class of Khmer textiles, are handwoven silk weft resist-dyed lengths. Khmer weavers are supremely skilled in their preparation, the variety of their patterns and motifs adding another layer to their fascination. The inspiration for their evolution is one particular Indian sourced silk textile, the ‘patolu’ (patola pl.) cloth. Patola, woven in the Indian province of Gujarat, are patterned by resist dyeing in both weft and warp. These filmy, colourful prestige textiles were highly desired by Southeast Asia rulers as the larger their collection, the greater their claim of power and prestige.

The Khmer term for a weft resist-dyed silk textile worn as an item of dress is sampot hol, where ‘sampot’ is the Khmer language word generically meaning ‘a length of cloth’, and ‘hol’ being the word for resist-dyed weft weaving. Hol is equivalent to the Malay word ‘ikat’ or ‘mat mee’ in Thai language. What uniquely distinguishes Khmer woven sampot hol from Tai, Lao, Malay and Indonesian silk weft ikat is that it is woven in the uneven twill technique resulting in one brighter and one darker side to the cloth, though by definition the pattern itself is identical on both sides.

Khmer sampot hol are prepared in two lengths – about 1½ metres or 3 metres long, both up to a metre wide. These are draped in two ways. The longer length is used for the more traditional style called sampot hol chawng kbun where the cloth is wrapped around the hips, the ends drawn through the legs from front to back with the ends secured under the waistband creating a voluminous pants style garment (KA 075/321/331/334/343/379/102). This style was and still is worn by both men and women in Cambodia. The shorter length called sampot samloy is worn by women as a hipwrapper in a wrapround skirt style (103). This style came into use in the early 20th century in response to the fashion of the Siamese court at that time.

The central field which takes up most of the design field space, is the location of the main area of pattern display. Older examples feature this central field encompassed by one or two borders running down the long sides. The end panels are a plain colour usually containing a few narrow stripes. Several categories of patterns and motifs are featured in the central field. As seen in the Zelnik collection one is a lattice structure, oriented diagonally, so forming diamond shapes. These may be filled with flower forms. Other patterns display simple patterns of flowers, stars, or spots laid out in geometric array. Specific patterns are created for wedding sampot hol and those to be used by novice monks on entering the wat. These require patterns based on nak (snake/dragon) forms or abstracted variations of these. The colour palette of Khmer hol textiles has been remarkably conservative since their first appearance in collections about 150 years ago. The scheme principally features red, yellow and deep indigo with touches of cream, green and blue.

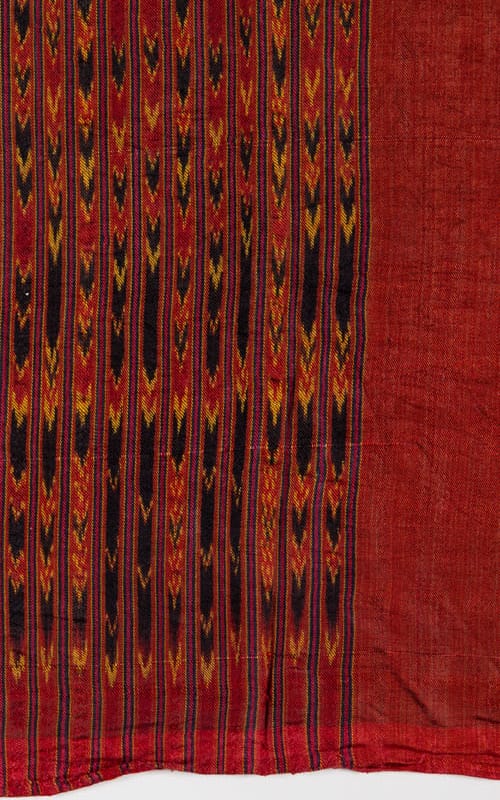

Another interesting pattern that features prominently in the Zelnik Collection is much simpler in structure. It consists of very narrow weft stripes patterned with simple weft resist patterns such as spots, dashes, chevrons or half chevrons. This striped pattern is called anlunh and the textile itself is sampot hol anlunh (277 detail /339/038/045/054/097). In some examples the stripe is bordered by a warp thread of contrasting colours twisted together. This gives a shimmering effect to the cloth possibly a substitute for a metallic thread.

Mon-Khmer communities have for centuries settled in the southern areas of Northeast Thailand (Isaan) particularly in the Surin area. Another community of Khmer, the Kui (Gui), live either side of the Dangkrek Mountains which form the border between Isaan and northern Cambodia. Those Kui living in the Surin area also weave silk weft hol lengths like the Mon-Khmer. Interestingly the Khmer weavers in Isaan have maintained their uneven twill technique even though in close contact with Tai-Lao communities of weavers who also weave silk in the weft resist technique but Tai-Lao weavers employ a plain groundweave so the colour hue is the same on both faces of the cloth. The Khmer in large part retained the traditional colour palette distinctive of weavers in Cambodia itself.

The Khmer hol anlunh, weft stripe hol, pattern is characteristic of Surin province in Isaan. ’. Photographic images of textiles with this fine striped pattern dated to the first decade of the 20th C show that Siamese court ladies and upper class Isaan ladies wore hol anlunh (the Tai-Lao version of anlunh is known as ‘lai kan’. Information published at an exhibition of Khmer textiles held by the Museum of the Bank of Thailand, Northern Region Branch Textile in 2009, lists sampot hol anlunh as one pattern of silk textile, albeit the lowest ranking, in a list of six pattern styles commissioned from Cambodian weavers by the Siamese court. It is possible that both traditions, the Khmer hol anlunh and the Tai lai kan are based on the Lao royal court silk hipwrappers which have very fine stripes containing tiny ikat patterns and which are further embellished with rich metallic supplementary weft hem borders.

A third style of textile in the Zelnik collection is the sampot lboek. This hipwrapper textile is patterned in a silk supplementary weave with small star-like motifs laid out in a precise array. The silk supplementary weft thread is usually the gold colour of the natural silk and resembles a metallic gold thread seen on textiles imported from India. This technique is a speciality of the weavers in the northwest of Cambodia who still excel in this technique today.

Hol pidan. Woven pictorial hangings for Buddhist use

Unique to the Khmer tradition is a handwoven silk weft hol textile called ‘hol pidan’. The word ‘pidan’ has the generic meaning of ‘ceiling’ in Khmer language. A ‘hol pidan’ is a pictorial textile distinguished by its Buddhist elements and motifs created by the hol technique. During the last century rare images appear in photographs showing hol pidan suspended under the roof of a wat. Donating gifts to the wat in the form of money, material gifts or even labour is a way of earning ‘merit’ for the donor. Painting Buddhist images on the walls or architectural elements of the wat earns merit for the male artist either monk or layman. This opportunity is denied to women but it seems that creating the same images by weaving pictorial panels and suspending these beneath the roof is a way that women can employ their artistic talents to attain merit. The pictorial elements of hol pidan vary greatly in complexity. Some supremely gifted Khmer weavers construct a composition with a sequence of elements, each different, illustrating episodes in the Vessantara jataka, or an episode in the life of the Buddha.

As each element of the composition is different, requiring specific resist dyeing preparation, this form of hol pidan is extremely challenging and only undertaken by the most accomplished weavers. Other hol pidan are composed of a sequence of 2 or 3 (031/293) and up to 20 repeats of simpler representative motif elements (292/352). Repeat patterning is much easier to achieve technically. There are some 30 pidan in the Zelnik collection. Some are singular examples, others are ‘twins’ and there are sets of ‘triplets’, ‘quadruplets’, and a set of quintuplets – that is 2,3, 4 and 5 hol pidan with almost identical patterns. Sets such as these demonstrate that one weaver prepared the resist dyed threads and wove them on a warp long enough to allow multiple hol pidan of the same pattern. Weaving multiples be they hol pidan or sampot hol on a single warp is the norm for handweavers. Setting up a warp is very time consuming and often additional help is needed, so weaving a number of finished lengths on one warp is economic in time and effort.

One particularly interesting pidan (KA 348) has two quite different compositions in the central field. What is particularly fascinating is that one section is derived from a full-length hol pidan – KA 292 and siblings /305/308/341 and the second from KA 301/ and siblings 084/265/307/311. This combination suggests that the weaver had resist dyed more weft thread than necessary for one pidan length so added it to a second to supplement its length.

Research into the origins of hol pidan indicates that their appearance is relatively recent, and coincides with the activities of the French inspired School of Cambodian Arts initiated in the 1920s. The Director, George Groslier, was determined to keep the practice of Khmer handcraft alive by encouraging Khmer craftsmen in silver, jewellery, wood and stone, and women in weaving to make items for innovative purposes beyond court and rural use. . Such items became highly collectable mementos for French civil servants stationed in the country as well as the ever-increasing numbers of travellers passing through. The Zelnik collection of ‘single’ hol pidan was acquired “…from [a] French doctor’s family, but also few pieces from the former Indochina French governor’s family and from two other families [whose] members worked in colonial administration” (personal communication 2016).

Tools of the trade

The Zelnik collection features a wide variety of handweaving implements. Despite the complexity and degree of difficulty of hol weaving, the handcrafted tools used to create them are simple and practical. This applies to pulleys, beaters, warp guides and warp boards as well as implements required for preparing the silk weft such as reeling wheels and hol tying stands. While the Khmer frameloom is an example of a loom familiar all through Southeast Asia, it does have distinguishing characteristics. These relate to its large size, and the particular placement of the warp board, warp guides and the warp-oriented treadles.

The implements in the collection range from rudimentary and undecorated, to highly decorated with relief carving lacquered in black, red and some with flourishes of gold. Examples of undecorated pulleys, reels, warp guides are probably those used by rural weavers far from larger centres where efficacy, not expensive decoration, is valued. The wheel used to collect the silk threads after winding off the cocoons, is supported on a bar which protrudes from an upright supported on a solid foot (4244). Warp guides come in pairs. They are in the form of a square beam with the middle section removed, with one end in the form of a head, usually a nak /dragon, or even a fish, the other its tail.

The form can also be a simple beam with decorative finials at each end (2465/2484/4360/4362). Hol preparation employs two identical hol tying stands of a specific form- a triangular base with a pole protruding vertically (2497/2495). The base is carved on the outer surface with designs familiar from bas reliefs as far back as the Angkor period. Operation of the loom requires pairs of pulleys connected to the treadles raising and lowering the heddle shafts as required (2584/2561/2599/4294). Shuttles, housing the bobbins with the dyed thread wound round, maybe open boat-shaped forms or maybe made of smoothed bamboo tubes, closed at one end with a nose-cone shaped element. Warp brushes with wooden hand pieces and bristles are used to separate the clingy warp threads.

During the 19th century the Siamese court required Cambodian weavers to produce silk weft hol patterned textiles to present to their courtiers. Who the weavers of these textiles were – rural Khmer women or court weavers or both – is not clear. The sampot hol woven for the Siamese court are distinguished from those for domestic Khmer use by the far more elaborate bands of patterning in the end panels. In the early years of the 20th century, George Groslier persuaded the Cambodian king to release his craftsmen and women into his newly established School of Cambodian Arts, Phnom Penh. Their brief there was very different to that of the court. They could now pass on their skills by creating the artefacts for the acquisition of people beyond the confines of the royal court, in true entrepreneurial spirit. It is significant that in the 21st century the art of weaving and its related technical skills are being appreciated by the arts agencies in Cambodia tasked with recovering, supporting and maintaining the skills of ‘intangible heritage’ creation into the future.

In the early years of the 20th century, George Groslier persuaded the Cambodian king to release his craftsmen and women into his newly established School of Cambodian Arts, Phnom Penh. Their brief there was very different to that of the court. They could now pass on their skills by creating the artefacts for the acquisition of people beyond the confines of the royal court, in true entrepreneurial spirit.

It is significant that in the 21st century the art of weaving and its related technical skills are being appreciated by the arts agencies in Cambodia tasked with recovering, supporting and maintaining the skills of ‘intangible heritage’ creation into the future.

Bibliography

Chandracharoen, Thirabhand, 2005, Tied Together: Khmer, Lao and Thai Mudmee Textiles,

J H W Thompson Foundation, Bangkok

Green, G. 2003, Traditional Textiles of Cambodia,

River Books, Bangkok

Green,G.2008, Pictorial Textiles of Cambodia,

River Books, Bangkok

Iwanaga, E. 2003. The Textiles of Cambodia,

Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka, Japan

Muan, I. 2001. Citing Angkor: The “Cambodian Arts in the Age of Restoration”, 1918–2000, unpublished PhD thesis,

Columbia University, New York

THE ZELNIK

TEXTILE COLLECTION:

MAKING AND MEANING

by Dr. Susan Conway

The Khmer silks in the Zelnik collection represent an important era in Cambodian textile history. Dated to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, they symbolize the work of women who raised silk worms, reeled silk yarn from the cocoons, dyed the yarn in the most beautiful colors and wove exquisite patterns. This collection also has rarity value. When the Khmer Rouge came to power in the 1970s they looted museums and decimated the silk industry. Only a few brave women continued producing silk in secret. *1

Silk weaving in Cambodia has a long history and probably predates Angkor. We rely on sculptures of the Angkor period (7th–14th century) and on Khmer temple mural paintings (late 18th–19th century) to confirm how textiles were patterned and the way they were worn. Khmer textile designs are generally categorized as of Indian origin, a theory that developed during the colonial period when the Indic was always esteemed over the indigenous. It is important to remember that although the Khmer lived on the periphery of the Indian empire and traded with India, they were capable of developing forms of art and craft, including textiles that express a discrete Khmer style. Khmer textiles captivated 19th century French artists like Rodin and Loti who captured the exotic nature of Cambodian dress and the movement of silk on the bodies of court dancers. Madame de Gaulle of France and Jacqueline Kennedy of the US added their appreciation in the 1960s. *2

The smooth, soft sheen of the textiles in the Zelnik collection can be attributed to the unique quality of the yarn. Silk worms were raised where the soil was suitable for cultivating mulberry and where there was an adequate supply of water. This was mostly in the vicinity of the rivers and streams of the Tonle Sap, Bassac and Mekong although silk was also produced in Cham villages in the province of Battambang and villages close to the border with Vietnam. At the time when the silks in the Zelnik collection were created, silk production was a major source of income for farming families who could, in a good year, raise enough cocoons to produce ten kilos of silk yarn. Khmer silk cocoons have a characteristic golden colour. Immersing them in hot water releases the filaments that are drawn up by hand (reeled) through a forked bamboo batten from between ten and twenty cocoons at a time to form a single silk strand that is wound onto a wooden frame wheel (as illustrated, p. 11). An experienced silk reeler can tell when the denier alters by the feel of the thread as it passes through her fingers. If it is thin, she automatically adds additional filaments. Roundness and regularity are important characteristics of Khmer silk thread and ensure an even color during the dye process and a smooth finish to woven silk. These qualities are celebrated in courtship poetry. Suitors compare the beauty of their sweethearts with the soft sheen of local silk.

DYES

The silks in the Zelnik collection are dyed in a range of colors produced from local sources, including tree bark, insect residue, leaves and flowers. Reds and pinks are from the sbaing tree (Caesalpinia sappan), seeds of jumpah fruit (Bixa orellana), from insect deposits leak khmer (Lakshadia chinensis), the teal tree (Dipterocarpus alatus) and Burmese rosewood (Pterocarpus indicus). Light and dark yellows are from prohut (Garcinia vilersiana), preah ankaol (Garcinia lanessani), jackfruit (Artocarpus integrifolius) and turmeric (Curcuma longa). Greens come from indigo (por baitong kchai), the bhas vine (Coccinia grandis) and the leaves of red and green pepper plants (capsicum). Light and dark blues are from por kiev (Indigofera tinctoria). Black (mcleur) comes from ebony (Diospyros mollis) the tros tree (Combretum trifoliatum) and phkol fruit (Mimosa elengi). Depth of color depends on the number of times the yarn or fabric is dipped in the dye bath. Secondary colors are achieved by overdyeing primary colors, for example a yellow then red dyebath creates orange. Not all women dyed silk themselves but took it to professionals in specialist villages, for example a thriving mcleur dyeing businesses flourished in Kandal province.*3 Other silk producers bought raw dyestuffs from local markets, made the dye vats that other women might share. Although the predominant color in the Zelnik textile collection is red, the total range of colors reflect an association with the days of the week, a tradition upheld by the court and senior officials. A Khmer homily states:

Red is worn on Sunday

Orange on Monday

Purple on Tuesday

Light green on Wednesday

Green on Thursday

Blue on Friday

Dark purple on Saturday *4

Weaving equipment and techniques

The Zelnik collection contains a range of Khmer weaving tools carved in wood by village carpenters, a testimony to their creative talents. Weavers use a loom with the warp tensioned around a board at the far end and held in place with carved warp board holders (tradok kdar) that are well represented in this collection. There is also a comprehensive range of wooden shuttles varying in size, small for weaving the finest patterns and larger shuttles for plain weave. They are carved in a curved shape with a smooth patina and can pass swiftly through the warp when hand- thrown. Other distinctive equipment includes pairs of carved wooden shaft pulleys, threaded with cord that attaches heddle shafts to loom frames.

The Zelnik collection contains silks that illustrate a comprehensive range of weaving and patterning techniques. The simplest technique is plain weave, passing weft thread over and under each warp thread, then under and over in the following line. To create variants the warp is a different color from the weft, described as “shot silk”. There are many textiles in the Zelnik collection where a black or purple warp is crossed with a red weft to create a shimmering effect as the silk catches the light. In other samples different color yarns are plied together to create one yarn that produces a similar two-tone effect. This plied technique is generally used to create narrow bands of color that border central fields of pattern.

Tying and dyeing weft threads into patterns before weaving is called hol in Khmer language. The warp threads are not patterned. A frame device with wooden dowels at each end is used to stretch out weft threads that are tied and dyed in sections to a predetermined color scheme or pattern. The size of the frame is set to match the weft; for most lower garments (sampot hol chawng kbun) in the collection, 60–90 cms wide. Banana twine is used for the ties.*5 Once the threads are tied in patterns to resist the dye, the yarn is taken off the frame, dipped in a dye bath and hung to dry. To produce a pattern of more than two colors, the yarn is retied and re-dyed or has extra ties added for each dye bath. Impregnation of the principle colors takes place in dye baths but small areas of dye can be painted on the threads with a brush. Touches of color added in this way can be identified in the Zelnik collection, particularly green. When the dyeing processes are finished, the banana twine ties are cut and the thread wound onto a bamboo frame ready for reeling onto bobbins.

To weave the pattern correctly in the weft, the bobbins must be kept in sequence. There are various methods to achieve this, one is to thread them in order on a length of twine with a bamboo stop at one end. The dyeing of complex hol patterns like many in the Zelnik collection, involves intricate tie patterns and numerous dye baths. If one examines the textiles closely, a guide line of a light color can be seen at the beginning of each row. When the weaver inserts a weft yarn she ensures alignment with the guide line and then the rest of the pattern will be produced correctly. Weavers say hol patterns are based on stylized flowers, fruit, plants like bamboo and insects and snakes. Geometric patterns represent diamonds, hooks, chevrons and stripes. The distinct quality of hol weaving is a faintly smudged look to the pattern, the result of dye slightly bleeding down the yarn.

The majority of hol silks in the Zelnik collection are woven in twill weave. Weft threads are passed over two, three or more warp threads to create a diagonal pattern. The most common form is a 1/2 or 1/3 twill. This technique creates silk fabric that drapes well, particularly suitable for garments worn by men (chawng kbun) and women (chawng kbun or pamuong) that wrap and tuck around the body. Twill weaving gives a clear and bright impression on one side of the silk and a duller effect on the reverse side.

The Zelnik collection also contains silks woven with a supplementary weft (sampot iboek). Thread is inserted in the weft between rows of plain weave, often handpicked row by row or using shed sticks inserted in the warp to set repeat patterns. Designs are based on local flowers like the morning star, lily and jasmine, the flowers of guava and pomegranate trees and chili pepper plants. They were pre-selected for gifts, yellow flowers for New Year and white flowers for elderly relatives. Gold and silver metal thread used in supplementary weft was expensive and is generally associated with members of the royal family, the court and court dancers.

Khmer Dress

A large percentage of the Zelnik collection consists of flat rectangular silks (sampot) approximately three meters in length. There is a wide plain silk border at each end, a central field of patterned silk and narrow borders along the length at top and bottom. To tie the sampot in kben style involves gripping the length at each end at waist height, crossing it around the body evenly from back to front, pulling the ends tight and knotting them. The excess cloth is rolled between the legs and inserted in the waist at the back. The width allows for covering the legs to below the knee or mid-calf. The wide plain borders at each end are tucked at the waist and the narrow borders along the length form a border for the pantaloon shape. The sampot was worn by men and women. Shorter lengths of silk in the collection are approximately two meters in length and worn in samloy style, as tubular ankle-length skirts wrapped and tucked around the body. Some have a waistband of cotton or silk in a separate color.

Religious Textiles

The Buddhist hangings (pidan) in the Zelnik collection are outstanding. They date from a period before the Pol Pot regime took power and most textiles of this quality were looted.*6 Produced in superb colorways they show remarkable attention to detail, requiring the highest level of skill to tie and dye the yarn. Each scene is repeated in the weft from six to over twenty times. Pidan were made as donations to monasteries, presented by individuals or groups. They were hung as canopies over statues of the Buddha and to create sacred space. Those participating in a ritual might sit beneath the canopy. The exceptionally fine hol patterns portray the Buddha and his disciples, followers and attendants in a stylized setting containing court and village architecture, regalia and scenes from nature. The spirit world is represented in idealized spirit houses and naga, the guardian spirit that controls fertility, wealth and wellbeing. *7

KA-060

HOL PIDAN

KA-084

HOL PIDAN

KA-293

HOL PIDAN

KA-341

HOL PIDAN

The most popular themes are from the Jataka stories, particularly the account of Prince Siddharta Gautama, the future Buddha who leaves his wife Princess Yasodhara and son Rahula sleeping in the palace, riding away on a white horse (KA–060). Celestial attendants lift the horse above the earth so that the sound of its hooves will not wake them. A white elephant is often included in this scene as a symbol of Khmer royalty (KA–084) and a peacock to represent the sun (KA–293). Other locations represented in the pidan include a forest where the future Buddha sits meditating beneath the Tree of Life (KA–341) or seated beneath a canopy while demons in the form of tigers come to tempt him (KA–352). The Buddha resists and after a series of trials achieves nirvana. He sits with legs crossed, his right hand touching the earth to bear witness to the defeat of evil (KA–295). Monks and celestial beings are often depicted in attendance. Pidan also portray men and women performing seasonal rituals. Elaborate candle stands, offering bowls and “trees of happiness” feature in these scenes that include mythological animals and human couples dancing in celebration (KA–031).

In summary, the Zelnik collection is a celebration of the beauty of Khmer silk and the art and skill of female weavers. The collection represents a belief system that incorporates Buddhism and spirit religion in a setting of Buddhist mythology and cosmology and it is a priceless visual dictionary of Khmer design. Students and admirers of Southeast Asian art should benefit from studying the collection, appreciating its significance as a representation of the best of Khmer culture.

As textile production becomes more standardized and mechanized the unique quality of indigenous, hand reeled and hand woven silk is appreciated as a rare and valued commodity. Whether the high standard of silk production and weaving that this collection represents, can be reached today is debated. Silk-weaving has seen a major revival with production increasing and providing employment for many rural women although the silk is often of coarser quality and weaving techniques less refined. If silk production is in transition, it is important to appreciate that this collection is a reminder that silk is not merely a commodity but a symbol of the rhythms of social and religious custom.

KA-352

HOL PIDAN

KA-295

HOL PIDAN

KA-341

HOL PIDAN

Footnotes

1 Heap, J., ‘Silk weaving in the Sihanouk Era’ in Hol: The Art of Cambodian Textiles (eds. Peycum, P., Ogawa, N., and Nishilikawa, J., Seminar Proceedings, IKTT and CKS, Cambodia 2004 (pp. 55–57).

2 Jeldres, J., The Royal House of Cambodia, Monument Books, 2003.

3 ‘Colors of Clothing’ in Seams of Change: Clothing and the care of the self in late 19th and 20th century Cambodia (eds. L. Daravuth and I. Muan), Reyum, Phnom Penh, 2003, pp209–217.

4 Siyonda, I., ‘Different Kinds of Cambodian Textile and Production Districts’ in Hol: The Art of Cambodian Textiles (eds. Peycum, P., Ogawa, N., and Nishilikawa, J., Seminar Proceedings, IKTT and CKS, Cambodia 2004 (pp. 33–36).

5 It is common now to use plastic thread but this does not give the same effect as banana twine.

6 Bernard Dupaigne noted in 2004 that only two samples survived in the Phnom Penh museum (Dupaigne, B., ‘Weaving in Cambodia’ in Through the Threads of Time, Jim Thompson Foundation, Bangkok, 2004 p. 28.

7 The naga powers the annual monsoon by dancing in the Universal Ocean, whipping up waves that create moisture to fall on earth.

The Khmer Silk Collection of Dr. Zelnik is one of the 3 most importants Khmer silk collection in the world. The two other are: the The Thai Queen’s Collection and the Collection of the National Museum of Cambodia / Phom Penh. The most rare and precious part of the collection are the Pidans, the pittoresque religious silk pieces.

© Silk for the Gods – Khmer Silk from the Collection of Dr. Zelnik © Dr. Susan Conway, Gillian Green, Dr. István Zelnik